When trolleys crossing the Lechmere viaduct had to stop for boats

Some of the gears that made the Lechmere drawbridge work, now covered in dust.

The opening of the Lechmere viaduct across the mouth of the Charles in 1912 meant a dramatic reduction in the time it took trolleys to cross the river, from ten down to just three minutes - except when a cargo schooner came through and the trolleys had to stop for the viaduct's drawbridge to go up to let it through.

It's been decades since the drawbridge last opened, but remnants of it still remain. If you're driving past the Museum of Science, you can see it on the Boston side, right next to the car drawbridge that still does open on occasion to let pleasure craft into and out of the Charles. Look for the tower and metal gateways next to the Green Line tracks up there.

Boston Elevated trolley crossing the bridge on Aug. 8, 1912 (From the Boston City Archives):

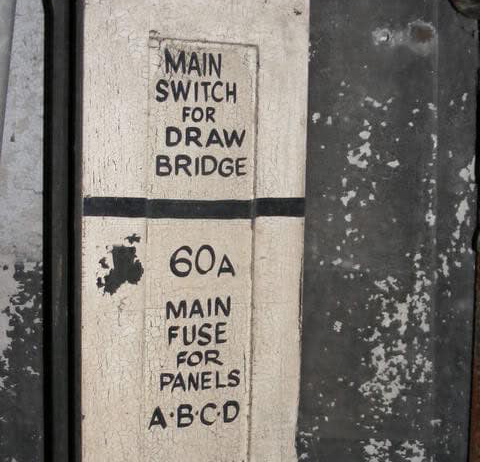

MBTA inspector Tim Murphy, who has a keen interest in Green Line history (back in his operator days, he was the driver who'd entertain riders with history lessons over the PA), recently got a look inside the tower, where the bridge men used to watch over the then newfangled electromechanical machinery that would raise and lower the drawbridge's two sections - after first raising bumpers on the tracks to keep any errant trolley drivers from plowing ahead into the raised bridge.

He reports the bumpers were put in after the 1916 Summer Street Bridge disaster, in which a trolley just kept going even though the span was open, plunging into Fort Point Channel and killing 47.

Just in case the draws didn't go up or down by themselves, this box used to have two wheels attached that four men needed to turn to get the bridge back to where it needed to be:

Lots of gears:

The tower today:

The tower, viaduct and dam in 1912 (Via BPL):

But what were all those schooners (and large barges) doing going up and down the Charles?

Although the river today is largely the preserve of smallish boats, back at the turn of the last century, the Charles was very much an industrial river. Cargo ships - many still using sails - traveled as far inland as Harvard Square to unload their cargo. Coal barges in particular were a common sight on the river, traveling to the Broad Canal, where Kendall Square is today, to fuel a power plant there.

The ships continued their journeys even after the Charles River Basin Commission completed its work in building the Craigie Street dam - where the Museum of Science is now - to change the area just up from the river's mouth from a brackish tidal estuary into the placid, lake-like Basin we know today.

The goal of that project was mainly to do something about the stench from all the sewage dumped into the river by ensuring that mudflats on both sides, but especially on the Boston side, were always covered by water, rather than having them left exposed to the air at low tide (along with that came the installation of a big ol' sewer to carry wastewater past the mouth of the river and into the harbor).

But the commission also ensured a channel was carved out of the river bottom as far as Harvard Square (with a recommendation to eventually continue that up to Watertown Square) to allow for commercial ships to continue plying the river.

The commission voted itself out of existence in 1910, just as work was beginning on the Lechmere viaduct - which, like the Tremont Street subway in 1897, was meant to get streetcars out of the carriage and now car-crammed road it paralleled. But just like Silver Line buses crossing Chelsea Creek today, the trolleys still had to halt for river traffic, at least of the taller ships.

A cargo schooner in Lechmere Canal in 1904, from the Charles River Basin Commission annual report

In its final report, published in 1910, the commission reported that in 1909 there were 30 wharves along Broad Canal and 12 along Lechmere canal, with another 8 along the basin itself. Also:

One of the largest cargoes to pass through the Lock was 2,012 tons of coal, and another consisted of 537,000 feet B. M. of lumber.

In an article that focuses on salt-water "whaleback barges" that sometimes carried coal up the Charles, the Cambridge Historical Commission writes that in 1893 64 sailing vessels and 61 barges tied up at wharves in Old Cambridge (Harvard Square) and Watertown.

According to a US Army Corps of Engineers report, as late as 1939, some 421,279 tons of freight came into the Charles, including the Lechmere and Broad canals, including sand and fuel oil.

Murphy says the last time the drawbridge was actually raised was sometime in the 1970s. The bumpers meant to keep trolleys from careening into the Charles stayed in place until 2011, when they were removed as part of some viaduct renovation work.

Ad:

Comments

Very cool!

Great article and pictures. Thanks, Adam!

Follow Tim On Facebook

He is always linking to good T related stuff.

How hard was it to thread a

How hard was it to thread a sailboat through the drawbridge if the wind wasn't blowing the right way?

It's too bad there's basically no more domestic water freight in this country. There are plenty of river and coastal barges in Europe. But here, the unions preferred to let their own industry die rather than compromise on work rules. Foreign ships can't carry freight between two American ports, so there's no water freight along rivers and coastlines. There are no American-flagged ships except where there's no alternative like freight ferries to islands.

Um, yeah ...

Funny how everything is always the fault of unions.

You might also want to take a look into the fact that while American passenger rail on the whole sucks, American freight rail is far more advanced than its European counterpart.

No, not everything. But this

No, not everything. But this is.

Unions did and do great stuff. In fact, I've been in one myself, as have several family members.

But in some cases, unions go too far at protecting their interests, even to their own detriment when the industry suffers and the jobs disappear.

I'm not making this up. Go down to the Seaport, look at the freight ships there (what few ships there still are), and notice what country they aren't from.

Look at the price of goods in Alaska and Hawaii.

Look at the number of major shipyards left in the U.S. (7), and how much of their business is for non-defense purposes (less than one third).

Look at how hard it was for international ships to provide humanitarian aid to Puerto Rico after Hurricane Maria, because Trump grudgingly waived the Jones Act for only 10 days.

Then pull up some pictures of Rotterdam or Hamburg. Look at the number of major shipyards in Europe (60). And look at the modal share of intra-Europe water freight (40%), compared with here (2%).

The majority of U.S. population is still clustered around coastal cities and rivers. People in Europe are transporting and buying the same stuff we are. What other explanation could there be?

You've established that water

You've established that water freight is not competitive in the USA, probably artificially so, but you haven't established it's because of unions. Do you have any examples of union actions that contributed to the current situation? I'm genuinely interested.

Europe may not be the perfect comparison because the continent has so many navigable rivers that extend deep into the interior. The United States has large areas, especially to the west, that can't easily be reached by water; this is part of what motivates our massive trucking infrastructure and the fossil fuel subsidies that go with it, with our highways more efficiently serving the functions waterways once did to the east and in Europe. Once freight is already on a truck it doesn't always make economic sense to stop and move it to a boat when you finally reach a river, especially when the truck is faster, cheaper, less damaging to the environment (somehow it's true), and on a road network that directly connects every interior destination with every international port.

Here's a paper that makes

Here's a paper that makes this very point.

http://digitalcommons.uri.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1125&context=m...

It's from 1979, but the situation hasn't changed at all since then, except further declines in the American shipping and shipbuilding industries.

Yes, plenty of the West isn't near rivers. But the population is. Almost every metro area is on a navgable river or the coast.

We Need More Local River Freight!

You could see it now, a barge at the Greeley Dam waiting for the locks to open so it could bring a few dozen hogsheads of pickled ginger to the dock by BU so all the Asian Fusion restaurants in Allston could have a dependable supply.

The boat could carry on up to the Weld Boathouse, where it would unload Chinese made Harvard sweatshirts to sell back to Chinese tourists at J August.

Then it could move onto Watertown Square where cases of throw pillows could be unloaded to waiting horse drawn carriages who would carry their wares to all the mommy needs something to do shops of Belmont, Lexington, Newton, Wellesley, Weston, and Wayland, but I guess unions ruined this fantasy too.

There is plenty of river traffic in the middle of the county, and up and down the Hudson. Ocean going ships can get to Albany. If one flies over Lake Erie and Detroit over a clear day, one can see ships in the water.

New England isn't built for river freight traffic. The aborted invasion of Quebec in 1775 is full proof that rivers only go so far here. Is it your goal to have New Balance move their shoes from Skohegan to Augusta and then barge them to Lawrence but only be done by merit shops? I guess we can bring back buggy whip makers whilst we are at it too.

Funny (I'm not being

Funny (I'm not being sarcastic). But despite these ridiculous examples, water freight is not what it could be in this country. And while there are a lot of factors, transportation issues are a major contributor to the severe decline in manufacturing and other industry, and making water freight difficult and expensive only contributes to that.

And when a container from another country arrives in Newark or Norfolk, why should its next leg have to be limited to a truck or train, when in some cases a domestic ship could take it to its actual destination?

actually there is a

actually there is a significant of freight on the Mississippi and also in the Great Lakes. Can't find the statistics now but it is there.

As I posted above, the modal

As I posted above, the modal share for domestic water freight is 2%. Intra-Europe it's 40%.

Columbia River

An enormous amount of grain and potatoes comes down the Columbia by barge.

Unions put all the stagecoaches out of business too.

If it weren't for that this anon imagines he could make a living.

That explains why

That explains why stagecoaches have a 40% modal share in Europe today.

Johnny, is that you?

Schooners and bridges

Cargo-laden schooners would be towed upriver through the narrow bridge openings by a variety of harbor tugs. I can’t imagine trying to sail through the Craigie Drawbridge.

Coal barges in the late 19th and early 20th centuries were often coastal schooners at the end of their working life, with their rigs cut down (few or no sails, and shorter masts). A single tug would often tow several of these at the same time.

I don’t know much about the history of navigation on Charles River specifically, but the above describes typical practices of other ports in the Northeast around the time the dam was built.

Both drawbridges over Broad Canal are now permanently closed.

Try Ol' Man River

Where do people go to get so ill informed?

It is obvious that the post-er has never seen the Mississippi River nor the Great Lakes for that matter

There is much water traffic [albeit of the nature of long strings of barges being pushed by tugboat like Pusher boats] on the Mississippi -- the barges carry grain, petroleum byproducts, chemical feedstocks and lumber to name a few cargoes

Currently on the Mississippi there are a number of vessels being tracked on-line including:

the DAN MACMILLAN with its associated barges Length 421 m [over 1200 ft] Beam 66 m [over 200 ft] -- that by the way is bigger than anything which has ever been in Boston Harbor including the JFK

https://static.vesselfinder.net/ship-photo/0-366984870-7f768b453f3bad136...

https://www.vesselfinder.com/vessels/DAN-MACMILLAN-IMO-0-MMSI-366984870

2% modal share.

2% modal share.

Why can't a container that arrives from China in Newark get transferred to a smaller ship to head to Boston? Because of protectionist regulations.

They would use other methods

They would use other methods besides the sails to move the ship on narrow rivers, such as: waiting for the tides to carry the ship in; sending a bunch of guys out in a rowboat to tow the ship; using the rowboat to drop the anchor ahead of the ship, then reeling it back in with the windlass; towing it from shore by rope; or towing it with a steam powered tugboat.

Lechmere Draw

Tugs would have been used. Something that is often neglected is the use of steam and later Diesel tugs to move sailing ships around in harbor. I remember the safety stops' being observed on the Lechmere Viaduct. The Coast Guard or the Navy might have something on when the birdge was last opened or when it was officially closed. I do remember an oil barge that was making deliveries to the power plant on the Broad Canal near Kendall Square in the 1960's then forgot about until much later and then saw that barge in service either in the late '70's or early '80's. Particularly noticeable in the iwnter when its path would be visible in the ice. As for upriver from Harvard, the Arsenal Street bridge WITHOUT draw is from 1925; the Harvard Square power plant of the Boston El was retired and demolished in the early 1920's for the construction of the Harvard Houses on the river. Dirty Little Secret of those buildings is that they're VERY modern from the mid-1920's!

Nice post!

Yes, very cool!!

The drawbridge for auto and truck traffic is still operational; I watched it go up a couple of years ago. Since it's at a lower level, closer to the water, it has to be raised for smaller boats. That means that the Green Line shuttle buses may get stuck waiting for it over the next year or so.

As late as the early 1970s, they were still bringing barges of coal through the lock here, to fuel the power plant on First Street just outside of Kendall Square, near the Longfellow.

Yep, still a functioning bridge

Construction couldn't begin on the Lechmere viaduct until after the dam was finished, because the state had a temporary bridge built for trolleys (and carriages and cars) basically where the viaduct is now; part of the dam project included putting a road on top of it. So not exactly a coincidence that the Charles River Basin Commission voted itself out of existence the same year that construction of the viaduct began.

I also saw one article (but, alas, didn't read it closely) about some controversy involving the fact that there were two sets of bridge operators (one for the road, one for the trolley) who got paid differing amounts for what was basically the same job (I think one group worked for the city, the other for the Boston Elevated).

Part of the traffic jam

Part of the traffic jam logistics getting everyone home from the 4th of July involves the road drawbridge. Taller boats have to wait until 1 am when the majority of cars have gotten out of the city, and then they raise the bridge.

Other non-functioning drawbridges

are on First Street and Memorial Drive (or maybe it's Land Boulevard by that point) over the Broad Canal. These would also have to be raised to allow a coal shipment to that power plant.

The dam drawbridge is definitely still in use. I've been stopped there numerous times on my bicycle. But I think only recreational watercraft still go under it.

Not this year, but...

The biggest non-recreational vessels every year are the barges carrying the fireworks for July 4.