The South Boston hill that helped seal a glorious Revolutionary triumph is named for a glorious failure

Workers used cranks at the bottom to adjust semaphores in Grout's system. From Swan.

South Boston's Telegraph Hill is where Washington ordered the placement of the cannons that drove the British out of Boston in 1776. You can't miss it - there's a monument there at the top of the hill. And yet the hill and the surrounding neighborhood is named for a failed business that barely survived for six years before its owner gave up and moved to Philadelphia.

In its own way, though, that business was also revolutionary: A system of relay towers that used semaphores and telescopes to speed shipping news from Martha's Vineyard decades before Charlestown-born Samuel Morse showed off his wire-based system. But Jonathan Grout Jr.'s "telegraphe" today is largely forgotten; his patent lost, no markers noting what he did. Only the name of the hill, and similarly named hills from Wood's Hole to Hull, remain.

All that's left of his patent is this entry:

Grout, born in 1761 in Lunenburg to Sarah and Jonathan Grout - a prominent colonial leader who worked with Washington on the Siege of Boston and later served in Congress - went to Dartmouth and became a lawyer in Belchertown. And then, somehow, he learned of work by Claude Chappe who, along with his brothers, built a system to speed military information across France in the 1790s, using a series of relay towers staffed by men with telescopes and semaphores, which could be put in different positions to relay numerical codes to be translated by anybody with the right code book.

With enough of these towers, France was able to reduce the time it took to get news from the fronts of its various wars to Paris from days to hours. The Chappes called their system a "telegraph" from the Greek words for "distant writing" - a name that would later be used to name the series of wires that Morse and others had built across continents and eventually even under the seas.

At the heart of the Chappe system were several wooden flags on poles, whose positions could be adjusted with cranks, corresponding to numbers. Workers at one tower would peer at a tower a few miles away, take down the numbers, then in turn adjust their semaphores towards the next system to relay the information. Although the speed of each individual number was slow - it took time to adjust the semaphores - the use of codes meant considerable information could be sent across long distances, at least during the day, far quicker than possible by horse or ship.

In one of the few overviews of Grout's work, in a 1929 talk at the Bostonian Society, William Upham Swan says Grout was granted a US patent on Oct. 24, 1800 for a similar system, which he intended to use to let merchants in Boston and Salem know which ships leaving Martha's Vineyard would soon come into their ports - in a matter of a couple of hours, rather than a couple of days, at a time when early notice of such arrivals was worth money to those merchants.

Two months later, the selectmen of the town of Boston offered him space on Fort Hill, but he declined. Instead, he built a series of towers from Martha's Vineyard - then a prominent shipping port, in the days before the Cape Cod Canal - to Cohasset. His first message went up the coast on Oct. 21, 1801, announcing the arrival of a ship called the Mercury from Sumatra at what is now Vineyard Haven.

The next month, workers finished a tower for Grout atop one of the Dorchester Heights - from which shipping news could then be relayed to his office at 112 Orange St., what's now Washington Street, where today's Chinatown becomes the South End and Roxbury, a little more than 70 miles from the harbor on Martha's Vineyard. His office had a clear view of the Dorchester Heights tower.

On Nov. 13, Swan recounts, the Boston Gazette announced:

The sloop Lucy of Boston from Baltimore and the brig Betty of Portland from Demarara have arrived at the Vineyard. The above despatch information was communicated to this town through fourteen different telegraphs.

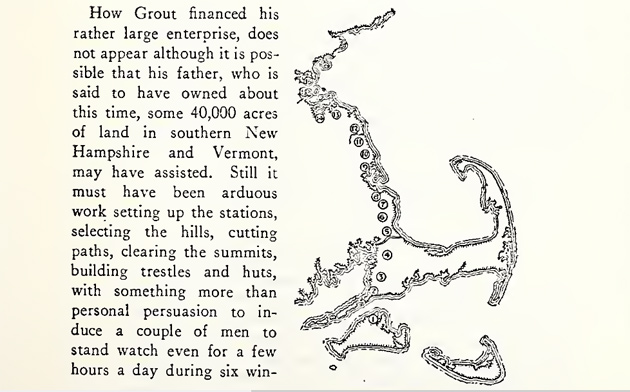

A network of optical telegraphe nodes:

A few days later, Grout put an ad in another paper, offering shipping news on subscription at rates between $2 and $100.

People began calling the hill Telegraph Hill.

In 1802, Grout moved his office from Orange Street to 75 State St. downtown.

In 1804, the town of Boston annexed what is now South Boston from Dorchester, and started mapping out new streets - including one called Telegraph Street, between Dorchester Street and Telegraph Hill.

But business never amounted to much for the telegraphe line. Swan writes that for awhile, Grout handed over control to an insurer and the publisher of a local newspaper, before returning to what had become a struggling business, unable to attract enough customers. On April 24, 1807, the network carried its last message.

Grout moved to Philadelphia, where he became a teacher and then a Swedenborgian. He died in 1825.

That was not the end of visual telegraphy in Boston. In 1820, Swan continues, Samuel Topliff, already running the thriving Merchants Exchange "news room" at Congress and Water streets - where captains of incoming ships and local merchants mixed to exchange news in what became a forerunner of today's Associated Press - came up with his own version of an optical telegraph, although one using three large black balls mounted on a mast, instead of the semaphores the Chappes and Grout used. In contrast to Grout, Topliff and John Rowe Parker, who took over the network, were able to make money from it.

But Topliff's network only had stations on Central Wharf - at the end of which the New England Aquarium sits today - Castle Island and Long Island, to get information about ships coming into Boston Harbor. The network was eventually extended to Point Allerton in Hull, Neither he nor Parker used any of Grout's towers.

In 1853, electric telegraph lines reached Hull and that was the end of the visual telegraph along Boston Harbor.

Ad:

Comments

So interesting!

Thanks for the history lesson! I had no idea how that name came to be.

Date that the telegraph stopped operating

You wrote "April 24, 2007". I doubt that this is correct.

Ugh, thanks!

Date-o fixed!

How was the patent lost?

Was there a fire, flood, or other disaster at the patent office that destroyed this record?

Good question

My first thought was the British set fire to the Patent Office in the War of 1812, but it seems they were persuaded not to.

Looks like there were two Patent Office fires

in 1836 and 1877, neither one caused by invading foreign armies.

Marshfield

The hill where the telegraph in wonderful Marshfield was is still called Telegraph Hill. 200+ feet up only 1/2 mile back from the ocean as the crow flies. It is the highest point just back from the ocean from The Pine Hills (the actual hills, not the real estate development) in Plymouth to Boston with the hill where the Standish Monument in the hate filled town of Duxbury is at around 180 feet.

By the way, a third name for the hill in South Boston besides Telegraph Hill and Dorchester Heights was Mount Washington. Hence Mount Washington Avenue, which is a street between Gillette and A Street that is a remnant of an early 1800's bridge built by real estate developers to get people to go to South Boston post annexation from the Town of Dorchester from Washington Street right about where the Pike and the Expressway intersect.

Also, the former Mount Washington Bank took its name because it was in South Boston.

Telegraph Street in South Boston is named for the Telegraph but other streets on the hill; Thomas Park, Gates Street, Mercer Street, and Knowlton Street are named for Revolutionary War Generals / High Ranking Officers.

Finally, the noted anti-Irish, anti-Catholic inventor, Samuel Morse, who invented the telegraph, was born in Charlestown. His house (still standing) is the The Cooperative Bank branch in Thompson Square.

Fascinating!

Thanks Adam!